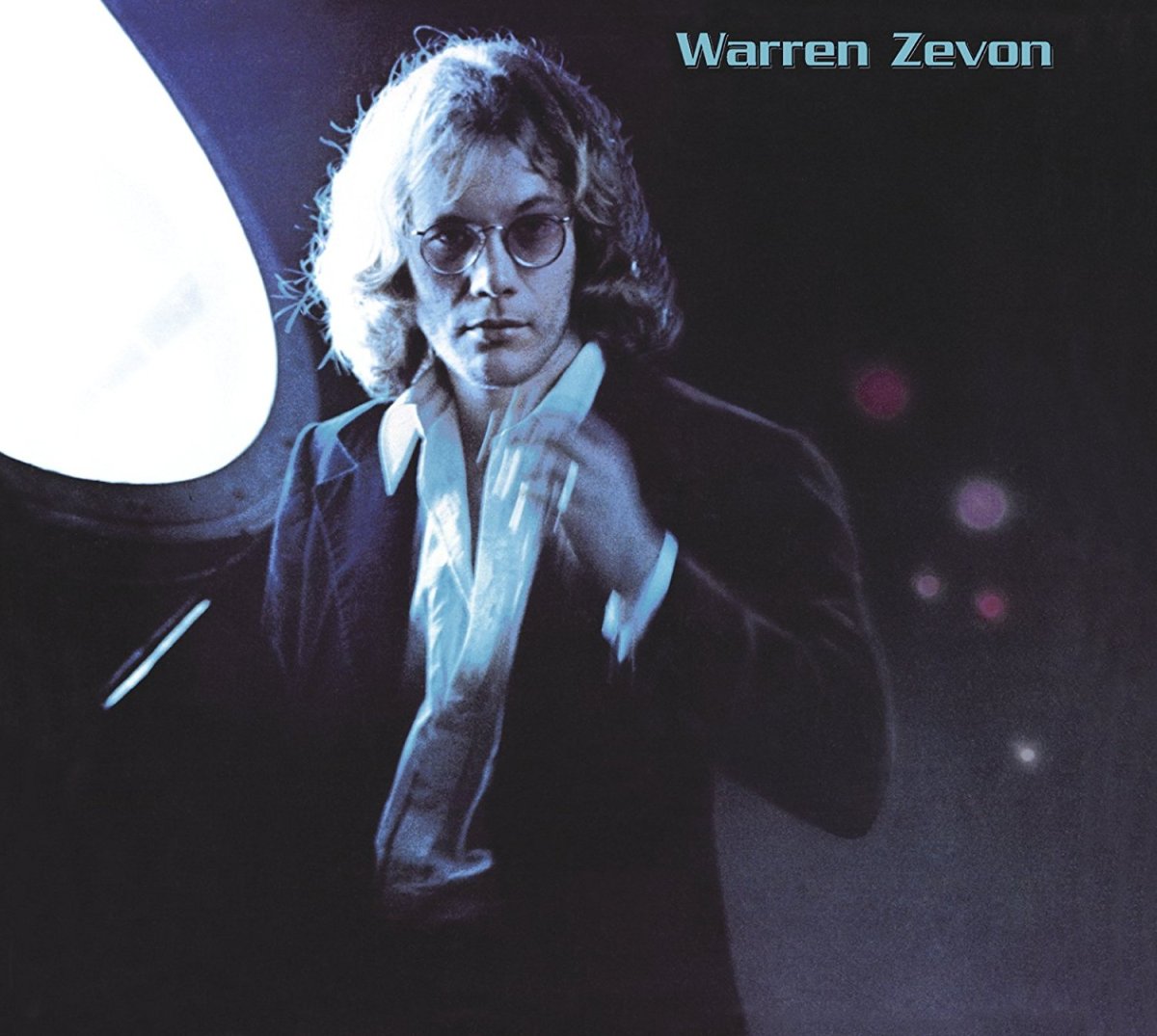

I love Warren Zevon’s music. To me, he is the type of musician that blends so much of what I love in art. Attention to detail, love of the outcast, desperation, loneliness, and an immensely personal touch wherein the work you make changes depending on where you are in life.

I could write about Zevon’s entire discography in this context, but I’d need the space of a book to do so. Instead, I’ll focus on one song in particular that I feel perfectly captures Zevon. The artist, the musician, the poet, the man.

[Warren Zevon’s] musical patterns are all over the place, probably because he’s classically trained. There might be three separate songs within a Zevon song, but they’re all effortlessly connected. Zevon was a musician’s musician, a tortured one. ‘Desperados Under the Eaves.’ It’s all in there.”

—Bob Dylan

“Desperados Under the Eaves” is many things. It is immensely evocative, chock-full of wordplay, and above all else a great song. I’d like to start by focusing on the poetic lyrics that Zevon penned.

Here are the lyrics in the first half of “Desperados Under the Eaves”:

“I was sitting in the Hollywood Hawaiian Hotel

I was staring in my empty coffee cup

I was thinking that the gypsy wasn’t lyin’

All the salty margaritas in Los Angeles

I’m gonna drink ’em up

And if California slides into the ocean

Like the mystics and statistics say it will

I predict this motel will be standing until I pay my bill

Don’t the sun look angry through the trees

Don’t the trees look like crucified thieves

Don’t you feel like Desperados under the eaves

Heaven help the one who leaves

Still waking up in the mornings with shaking hands

And I’m trying to find a girl who understands me

But except in dreams you’re never really free

Don’t the sun look angry at me

I was sitting in the Hollywood Hawaiian Hotel”

The first stanza/verse paints a picture of a broken man, who clearly loves drinking. The added flair of alliteration forces us to pay attention to the words in this part, rather than the music. Zevon also offhandedly mentions that he’s been to a gypsy psychic, showing us a glimpse into his thoughts on the supernatural.

As we move on into the subsequent verses, our picture of this paranoid alcoholic is sharpened. Zevon also, in a clever rhyme, reminds us that sometimes the spiritual (mystics) and secular (statistics) converge. Of course, in this case, it’s an agreement on apocalyptic prognostication, one that will still leave Zevon bitten in the behind when all is said and done. This is a motif of the first half, everything coming together against Warren Zevon. The world must just be against him personally.

There’s also a great deal of religious imagery in this opening half. Obviously there’s the “heaven help” line, as well as the the appeals to both mystics and a gypsy. But I want to focus on the Sun, and the trees that “look like crucified thieves”.

In the gospels, Jesus is crucified along with two thieves (in Luke these are the Penitent and Impenitent thieves). This line changes the meaning of the angry Sun; instead of referring to an angry ball of hydrogen and helium, it’s referring to the homophone version (Son), which when paired with crucified thieves, means Jesus.

Thus, when the Son looks angry at Zevon specifically (“don’t the sun look angry at me”), it’s referring to an angry God, one that Zevon thinks is singling him out. This plays into the persecution complex that is plaguing him throughout the song. Even if the world is ending, the motel will still be there to collect from him, because he just can’t catch a break. He can’t find a girl who “understands” him, and this complaint is lumped in with the shaking hands that indicate his alcoholism. He can’t find any freedom but in his dreams, and it’s all because the world, and God, is against him.

“Desperados Under the Eaves” has been called one of Zevon’s most personal songs, which makes sense. A struggling man, who thinks the world is against him. An alcoholic, waking up in the morning with “shaking hands” and a vague recollection of what some gypsy told him as he stares into his coffee. It’s easy to see how Zevon, who at the time of writing hadn’t released a major studio album yet, and who was an alcoholic abuser who did awful things and was a generally shitty person, could be seen in these words. He’s justifying his own failures and shitty actions by blaming them on an angry God.

If “Desperados Under the Eaves” were purely literary, I clearly still think it would be worthy of praise, even if the message of the first half is comically misguided. But it exists as a song, and it is musically where it shines.

Thus far I’ve focused on the first half, and in that section the words dominate. But this shifts as we move to the latter half, and something else takes over.

“Desperados Under the Eaves” is 288 seconds long. Here are all the words in the second half of the song:

“I was listening to the air conditioner hum

It went mmm…

Look away down Gower Avenue, look away”

Of course, if that was all that there was to the final 144 seconds, I wouldn’t be writing this piece. Those seconds contain a hymnal quality, with the sweeping strings, layered harmonies, and incantatory repetition of “Look away…”. It is one of the most hauntingly beautiful arrangements I have ever heard. I am not a musical theorist. I can’t give you the concrete reasons as to why it is brilliant. People way smarter than me (Dylan, Springsteen, Carl Wilson and Jackson Browne, the latter two being a part of the “Look away” harmony) recognize how incredible it is, and I’ll take their word for it.

All I can tell you is that as it crescendos and eventually fades, it arouses emotions in me that I didn’t know I could feel. Its beauty moves me in the special way all of us have been by music—i.e. a way that as of yet hasn’t been put into words, and which I highly doubt ever will.

But what makes “Desperados Under the Eaves” truly genius is in the way it frames this beauty.

This gorgeous, maddeningly perfect ending is all supposed to be coming from a humming air conditioner, in a tacky, themed motel. We have all seen these air conditioners, have all felt their mediocre cooling abilities, have all heard the rattle and hum of one of life’s least consequential items. Zevon’s genius is that he gives said item the ability to conjure the holiest of sounds—to be the source of one of the most beautiful things you can ever hear.

When Aretha Franklin passed away earlier this year, I read an amazing piece by Rembert Browne that talks about her album, Amazing Grace. In it, he says:

“Technically, Amazing Grace is art at its highest form, the work of a bona fide musical genius at her peak…For as long as I can remember hearing these songs…there’s been a moment, on each song, that Aretha does something that makes me believe in God.

More than any sermon, any text, or any life moment, it’s Aretha that keeps me a believer, in something…Over the years, it was this album that provided a light. That assurance you need in your life, that things will eventually be OK.”

I have gone back and forth on my spiritual beliefs more times than I can count. Even as I write this I grapple with the idea of a higher power, the concept that there is something out there for us that binds us all, that gives us that assuring light.

I can’t go as far as to call myself a believer. I’m not. But in the moments when I fancy myself a believer, in the moments when I do think there is a higher power, I find it in the smallest details. In the crevices and crannies that on any given day seem innocuous. If there is a higher power, it comes to me in the strangest ways. It’s in an autumn breeze. In the facial expression of a loved one. A smell from an open window. The feeling of warm water on your hands. The tiniest things that reach out to you and remind you why life is this cosmically beautiful thing, which–higher power or not–we’re lucky to be living.

Warren Zevon would have never written a song that is explicitly about a religious experience. He thought himself too cool, too swaggering, too devil-may-care.

But I think Warren Zevon heard his higher power humming to him in the Hollywood Hawaiian Hotel. It’s why religious words and imagery pervade throughout. It’s why his complaining about the world’s bias against him ends. It’s why we’re left to rise up with music that would move heaven itself as we look away, down Gower Avenue. He heard something speak to him, reassure him that everything would be alright. He heard it in that beautiful hum.

It’s why every time I hear that hum, I find something new to believe in.

[…] down Gower Avenue.” I quickly realized it was a nod to the Beach Boy as a harmony vocalist onone of Dylan’s favorite songs, 1976’s “Desperados Under the Eaves” by Warren Zevon, which climaxes on that same […]

LikeLike

[…] Avenue.” I instant realized it used to be a nod to the Seaside Boy as a harmony vocalist on one in all Dylan’s popular songs, 1976’s “Desperados Beneath the Eaves” by Warren Zevon, which climaxes on that […]

LikeLike

[…] down Gower Avenue.” I quickly realized it was a nod to the Beach Boy as a harmony vocalist on one of Dylan’s favorite songs, 1976’s “Desperados Under the Eaves” by Warren Zevon, which climaxes on that same line about […]

LikeLike

[…] down Gower Avenue.” I quickly realized it was a nod to the Beach Boy as a harmony vocalist onone of Dylan’s favorite songs, 1976’s “Desperados Under the Eaves” by Warren Zevon, which climaxes on that same […]

LikeLike

[…] Avenue.” I quick realized it was once a nod to the Seaside Boy as a group spirit vocalist on one among Dylan’s accepted songs, 1976’s “Desperados Underneath the Eaves” by Warren Zevon, which climaxes on that exact same […]

LikeLike